Hit the Road, Jacques

Save the Tracks Today, or Canadian Trains Won't Be Coming Back No More...

I hope you’ll excuse my silence. Since I started writing these dispatches in February of 2023, I’ve stuck to a more-or-less weekly schedule, but things got complicated over the holidays. My wife and I have two elementary-school-age boys, and a province-wide teachers’ strike here in Quebec means that they’ve been home since Nov. 23. The strike is now resolved, and they’ll be going back to school on Tuesday, but, what with our child-care issues, and the holiday round of family visits, it’s been a challenge finding time to write.

What’s more, I’ve been trying to figure out what to do about Substack’s “Nazi Problem”1. It’s a conundrum, and in truth, I’m questioning whether to keep writing on this platform at all. That said, while I’m mulling my exit strategy, I seem to be here again, obsessing about sustainable transportation, in all its forms.

For the last couple of weeks, I’ve been thinking a lot about intercity rail transport in Canada and the United States. To tell the truth, it’s never far from mind: I live in a permanent state of envy of other nations’ passenger rail networks, especially given the post-Covid rail renaissance that’s sweeping Europe. (You can read more on the staggering range of high-speed and night-train options coming on-line across the Atlantic in this New York Times report.) Last year, I reported on a trip I took on a Via Rail train from Montreal to Toronto, and my frustrations with our national carrier’s chronic lateness, lack of coverage, low frequencies, and inexcusable slowness. When the parlous state of rail in Canada comes up, I’m acutely aware that I have a tendency to go from being a poised middle-aged father to a frothing-at-the-mouth, too-much-information, sarcasm-riddled ranter. Chalk it up to a lifetime of disappointment, and the fact that every federal government since my youth has reliably failed to improve service.

I guess part of me hoped Justin Trudeau and his Liberals, who came to power in 2015, might be the ones to deliver something on this file. His administration has a good reputation abroad, because he has a talent for always saying the right thing, in pleasingly mellifluous tones. Believe me, though, things are different at home: under his watch, Canada’s carbon emissions have increased, tarsands oil exports are up, most indigenous communities still don’t have safe drinking water, and we remain as car- and airplane-dependent as we were a decade ago. (Of course, things would be—and probably will be—much worse under the Conservatives. But that’s pretty cold comfort, eh?)

So this week, I won’t repeat my diatribes about Canada’s failure to grasp even the low-hanging fruit of providing frequent, fast rail service from Windsor to Quebec City (a 1,150-km, or 715-mile “corridor,” along which half of this country’s population is clustered). But I will direct you to a well-reported and fascinating feature in the December-January issue of Canadian Geographic, by Edmonton-based journalist Tim Querengesser. “Losing Track” digs into Canada’s long history of rail-building, and the fact that, until it was bound together by steel rails, Canada was more a notion than a nation. (Querengesser doesn’t shy away from the reality that the transcontinental railway was a tool of colonialism, which is why First Nations activists strike such a meaningful blow when they blockade the tracks across their territories).

The trains haven’t completely stopped running, but these days, most of them are carrying freight. A lot of freight: up to four kilometers of tankers, and hoppers, and flatcars, rumbling through prairie towns, forests, and densely-populated downtowns. There’s nothing wrong with moving goods by freight train: in fact, in the US, 28 percent of goods are moved by train (much more than in Europe, where they tend to go by truck), with freight trains accounting for just two percent of transport emissions. The problem is that deregulation and consolidation mean that just half a dozen companies carry almost all of the continent’s rail freight, and government oversight is ridiculously weak; in Quebec, the center of a small town, Lac-Mégantic, was vaporized by a runaway freight a decade ago; last year, a freight train derailment caused a toxic mushroom cloud to rise over East Palestine, a village in Ohio. Often there are only two employees on these massive land barges, and industry is lobbying to get that number down to one.

For a quick, funny, but also terrifying crash-course (ahem) on the issues, try to watch John Oliver’s Last Week Tonight segment on freight trains, which is summarized in this Guardian article. It turns out the new, American-devised industry standard is something called Precision Scheduled Railroading, which boils down to running fewer, but much longer, trains. In spite of the name, PSR-standard freight trains, (unlike passenger trains) are not subject to schedules or timetables: if you’re a freight train, you go when you go, and everybody else has to get out of the way. That’s why Amtrak and Via Rail, which share tracks with the freight companies, so often get sidelined by endless lines of tankers and grain cars, moving at a leisurely pace. As Oliver points out, too often they’re completely stationary, for up to 24 hours—usually blocking a road full of frustrated drivers (some of them behind the wheels of ambulances and fire trucks).

In fact, according to this CBC article, Via Rail owns just three percent of the tracks its trains currently use. (In contrast, freight operator Canadian National, aka CN, owns 83 percent). One solution would be to “double-track”: ie, lay new rails, ideally suited for lighter, high-speed electric passenger trains, in such high-population corridors as Quebec City-Windsor and Edmonton-Calgary. As a nation, we’ve been working on this option for years—commissioning endless multi-million-dollar studies—but now there seems to be some movement on high-frequency, if not high-speed, rail in eastern Canada. (Hark: do you hear the sound of my breath, not being held?)

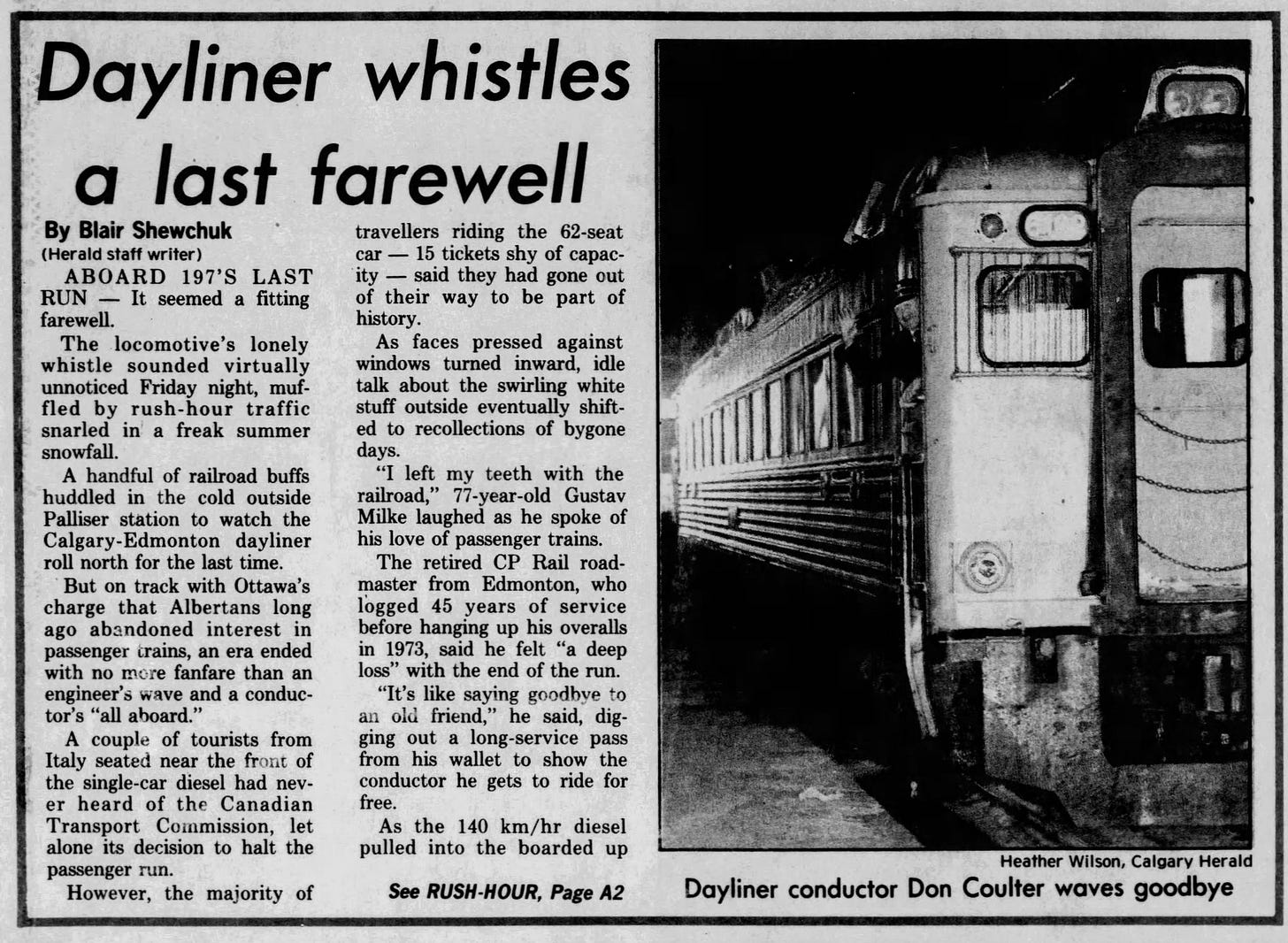

What Querengesser’s feature makes clear is that while all this overreaching inaction has been happening in the foreground, in the background, historic rail lines have been disappearing, probably forever. The article charts the disappearance of the one passenger line on Vancouver Island; the last Budd car (a self-propelled, 1930s-vintage rail-bus diesel hybrid) ran from Victoria to Courtenay in 2011. (And I’m kicking myself for never taking that ride!) He also writes about the Dayliner Via Rail service between Calgary and Edmonton (amazing detail: in the 1930s, Canadian Pacific ran steam locomotives on the route capable of 180 km/h), which made its last run in 1985 (see below).

I’ve written about one route that’s almost certainly gone forever: Le P’tit Train du Nord. This was a train from the heart of my Montreal neighborhood, Mile-End, to the Laurentian Mountains (the ruins of the station are a few blocks from our apartment). It’s been turned into a 200-km bicycle-hiking-cross-country-ski-trail of surpassing charm; I’ve ridden the entire length of it with my son, an experience I wrote about here. As much as I value the recreational trail, I would kill to have a train close to home that took me and my family directly from the city to ski and cottage country.

“Once passengers are gone,” writes Querengesser, “pressure mounts to pull up the tracks and develop the land for other purposes. When that happens entire rail corridors can be lost to history…” And he makes it clear that a lot of the routes have been abandoned relatively recently, including the 144-year-old link between Brampton, west of Toronto, and Orangeville, which was mothballed in 2011; the rails are now being removed.

The restoration of the Calgary-Edmonton link, a classic no-brainer (100,000 vehicles drive the highway every day, along a corridor that serves 70 percent of Alberta’s population), is currently being tech-jacked by hyperloop vapour merchants, who, like Elon Musk in California, will almost certainly ensure that nothing really useful—like high-speed, or even relatively high-frequency, rail—will actually get built.

In the gloom, glimmers of hope: most usefully, service to Quebec’s Gaspé remote peninsula may be restored, and First Nations are making a solid case for the “Bear Train,” to serve communities in northeastern Ontario that not even roads reach now.

Querengesser’s feature ends on a note of cautious optimism—a classic Canadian move. As a card-carrying Canuck myself, I don’t want to accept the idea that the future of this country is all roads-and-runways. Though, given our current leadership, which has perfected the art of talking out of both sides of its mouth on anything related to the environment, I don’t really see it going any other way any time soon.

Thanks to Jonathan Davies of Ottawa, who tipped me off to the article. Good spotting: this was mos-def a must-read for a train-lover of my ilk.

In last week’s dispatch, I wrote about the fact that Substack is infested with Nazis and white supremacists, and that its founders have decided to do essentially nothing about this horrible reality. I think they should: Substack is a publisher, and a publisher can choose which writers it’s going to publish. I don’t buy the “Nazi Bar” argument (which runs: let one Nazi into your bar, and soon your establishment will be filled with nothing but jackbooted goons)—that may be true of a saloon, but this is not a space in the real world where thugs can beat up people with their fists. It’s an online space with 17,000 writers, many who will be writing things I strenuously disagree with, and even abhor. But I draw the line at Nazis and Fascists, because history: time and time again, they’ve exploited democracy and freedom of expression to rise to power to dismantle said democracy, and censor everything but their own hate-based version of reality. (This is especially relevant in a year when a proven, democracy-disdaining, and dismantling, authoritarian, Donald Trump, is likely to be in the running for the US presidency.) Given that Substack isn’t facing up to this fact, I’m working on an escape plan. This could take time, and because people have paid money to receive these dispatches, I’ll be publishing them in this space until I can figure out how to transition out of here.

Please unsubscribe me