Take a Ride on the P'tit Train du Nord.

How to Take a Car-Free Vacation in Canada's Wilderness

One of the challenges of not owning a car is finding a way to get out of the city. We live in a walkable neighborhood in Montreal, where car ownership is actually a nuisance—what with ever-changing parking rules, snow removal, and street cleaning, people are constantly forced to shift their two tons of glass, metal, and plastic to avoid getting tickets. We do almost everything by bicycle, metro and bus, and by “shank’s mare” (the term my late Irish papa used for going by foot).

The problem is, our neighborhood is gripped by the usual urban tangle of hideous highways and daunting bridges and tunnels, which are further swaddled by tedious expanses of suburban development. We occasionally book a carshare when we’re going camping or to a cottage, but I find the fact that we have to succumb to the dismal logic of motonormativity—a term I explain in this dispatch—more than annoying. Getting to green places shouldn’t force you to pollute.

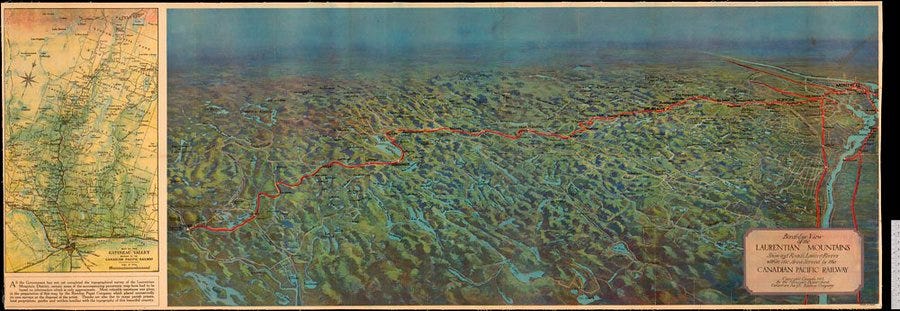

A century ago, getting away car-free wasn’t so much of a problem. There was a CPR station in the heart of Mile-End—it stood until 1970—the starting point for city folk who wanted to go to the Laurentian Mountains, north of Montreal, and beyond. The train was something of a legend—the “P’tit Train du Nord,” which ran in summer to take people to their lakeside cottages, and in the winter to get them to ski hills. Today, the trip to the Laurentians involves a northward drive along the pollution corridor of Highway 15, which is often clogged with impatient Montrealers. (Two weeks into 2023’s “construction holiday,” as the late-July, early-August vacation period is known, 22 people have died in vehicle crashes on the roads of Quebec—a new record.)

There is another way. Two years ago, my eldest son Desmond and I hopped on our bicycles, and, after humping them onto a metro train, and then a commuter train, pedalled 201 kilometers north from St. Jerome to Mont-Laurier. The two-day trip was one of the best, and most memorable, father-son travel experiences we’ve had. (I wrote about it in this Wall St. Journal travel feature.) We followed the former route of the P’tit Train du Nord, which is now the name applied to a trail used by cyclists and walkers in the summer, and by cross-country skiers in the winter.

Last week, we decided to follow in our own footsteps. It was a spontaneous decision: the weather forecast was good, and I found a good same-day price on a hotel room for the end of our ride, so we threw a change of clothes and some protein bars in our backpacks, along with tools and spare inner tubes, and booked it for the nearest métro station.

The trip started on the platform of the Rosemont station of the métro’s Orange Line. (You can wheel bikes onto the front car of Montreal métro trains for free.) Then a straight shot north to the De la Concorde station, which got us to Exo, as the commuter-rail network in the Montreal area is known. I bought a ticket at a machine on the outdoor platform ($6.80; Desmond, who is 11, still rides free), and then we hoisted our bikes up onto the train and attached them with bungee cords so they wouldn’t get tossed around during the trip. Exo serves the suburbs of Montreal with big, double-decker diesel trains, which aren’t wheelchair accessible, and seem radically overbuilt for the job. (Like Via Rail, they share many stretches of tracks with freight trains; if they had their own tracks, lighter electric trains would be easy to run.)

It was a holiday Sunday, and there were more bicycles on board than I’d ever seen before. We disembarked at St. Jérôme, the end of the line, and joined a crowd of cyclists—as well as people in mobility scooters, on rollerblades, and riding e-bikes—heading north. We followed a section of tracks, long dormant, that steered us through an arch that marked Km 0 of the trail. The sky was blue, temperature in the low twenties, and we were already old hands at the trail’s opening stretch, which was well-paved and level. Every three or four minutes, another black-and-burgundy milepost flashed past. At Kilometer 5, we paused to clamber over the rocks overlooking the churning rapids on the Rivière du Nord, which was running higher than we’d ever seen it.

Part of the P’tit Train’s charm is the way its former whistle stops have been preserved and repurposed. The original rail line, built between 1876 and 1909, was part of the Catholic church-led “colonization” of the Laurentian Mountains by French-Canadians. By the 1930s, the P’tit Train du Nord had become a celebrated party-train, bringing city-dwellers for weekend jaunts to some of North America’s first ski resorts. Construction of a highway killed off demand for the passenger rail service, which had its last run in 1981; the “rail-to-trail” was inaugurated fifteen years later. Today, the old Queen Anne and Gothic revival-style stations have been remade into service centers. Most have charging stations for electric bikes, stands with tire pumps and tools for quick repairs, and water fountains and restrooms.

As pavement gave way to gravel (just over two-thirds of the P’tit Train is surfaced with easy-to-ride asphalt), we decided to stop for lunch at the outdoor terrace of Le Malpache at Val-Morin station, which served nice seafood tacos and artisanal beers.

North of Val-Morin, the crowds started to thin out, as we left behind the daytrippers, and settled into clocking some serious mileage (er, kilometerage). Two years ago, Dez found this a challenge, and was visibly flagging at the 50 kilometer signpost. This time around, the complaints were fewer, and I found myself having to push myself to keep up with his pace. (As a father, I sense I’m going to have to get used to this.) We whooped and made wolf-calls as we coasted through well-graffitied tunnels, paused to watch teenagers doing backflips off a footbridge into the Rivière du Nord, and rejoiced after Ste-Agathe-des-Monts, where the trail began a long downhill stretch that allowed us to coast at 20 km an hour. We got to Mont-Tremblant around seven at night. The only difficult part was four or so kilometers we had to do on the country highway to Lac Ouimet, where our lodge was located; the road lacked paved shoulders in some parts, so we had to dismount and walk our bikes for long stretches.

In total, we’d done 83 kms of the P’tit Train—with detours and the final approach to the hotel, about 90 km. We were more than ready to plunge into the indoor pool and have a long soak in a hot tub at the hotel (the next morning, I threw myself into a cool Canadian mountain lake, one of the world’s best wake-ups).

The following day was a Monday, and the trail back was far less crowded; in fact, for long stretches, we were entirely alone. I coaxed Dez along with promises of Gatorade and snacks; we finally decided to stop for a full lunch, of wraps, potato salad, and homemade lemonade, on the terrace of the Café de la Gare at Kilometer 25, in the former station of Ste-Adèle.

There, among century-old posters for the local ski lodge, I saw this framed black-and-white photo of passengers aboard the P’tit Train du Nord. And that made me think.

Why is access to a private car seen as a prerequisite for vacations in Canada’s wilderness? It didn’t use to be that way. As a family, we could have packed up our things and walked a few blocks to the Mile-End Station (where trains could also take you to Ottawa and Quebec City), taken a beautiful ride through the woods, and then hired a jitney—a local taxi—to take us the last few kilometers to a cottage, a hotel, or a ski lodge. This was also the way people visited the Canadian Rockies, with cross-country trains stopping at Banff, Jasper, and Lake Louise—at the latter location, to be taken by funicular to the stunning lakeside railway hotel.

“Rail-to-trail” is the term for taking old railway lines and turning them into hiking, cycling, and skiing trails. As much as I enjoy the P’tit Train in its current incarnation, I would be the first to support a return to real rail service from the heart of Montreal into the Laurentians. (And why not a train to the Eastern Townships, our little patch of New England east of the city?) And trains don’t have to preclude trails—trackside paths, which already exist alongside many Exo routes, could be extended north to Mont-Laurier. In the Anthropocene, with wildfires charring much of Canada’s boreal forest, we need to be thinking about alternatives like these.

We got lucky on the way home—our Exo train made a stop at the old Parc station, which is only a couple of kilometers from our home. (For some reason, trains don’t stop there on weekends, which is why we had to start our trip on the métro.) Because I’d cashed in a free night from a loyalty program, our night at the hotel was free, so the whole trip cost under a hundred bucks ($15 for train fare, the rest for meals and snacks). We finished feeling fit, rugged, and more than a little proud of ourselves.

Being forced to drive a car, especially along frantic highways, always makes a good day into a bad one for me. This is the kind of vacation I like—active and challenging.

Dez and I are already trying to figure out ways to do another one—this time using Montreal’s newest-born transit system, the REM. Watch this space for further adventures!

Great piece! I did a similar outing with my son Noah last year. This year I did two separate outings in the Montérégie, which is quite accessible without any public transport link. The hard part is getting on the Jacques-Cartier bridge and then finding the Route Verte on the other side of Longueuil. Chambly and St-Jean-sur-Richelieu are easily accessible within a day's ride (a day trip to Chambly is quite feasible), and Granby on the edge of the Estrie is also a reasonable day ride. With my daughter we passed through the Mont St-Bruno park to get some real nature.

Great article, and glad you made a stop in Sainte-Adèle! A big issue we have in the region is that despite (or maybe because of) the P'tit Train du Nord, and unlike in other regions like Estrie, facilities for active transport are seriously undeveloped, as you noticed in Mont-Tremblant... and, actually, Mont-Tremblant probably has the best bicycle network of any of the towns along the trail. There's also the issue that the rail trail is great for recreational use but suboptimal for commuting since (a) in theory, you're not supposed to go faster than 22 km/h on it and (b) it's a ski trail from November to April :)

At some point with the population explosion in the region we will have to give more serious thought to sustainable transport, whether it's buses on the 117 (which exist... but barely) or bringing back the train. The 117 is a more useful corridor since that's where all the development has happened for the last 70 years or so.