Parks are Not for Cars!

Montreal's Mont-Royal Is Scrolling Back to 1876—and That's a Good Thing.

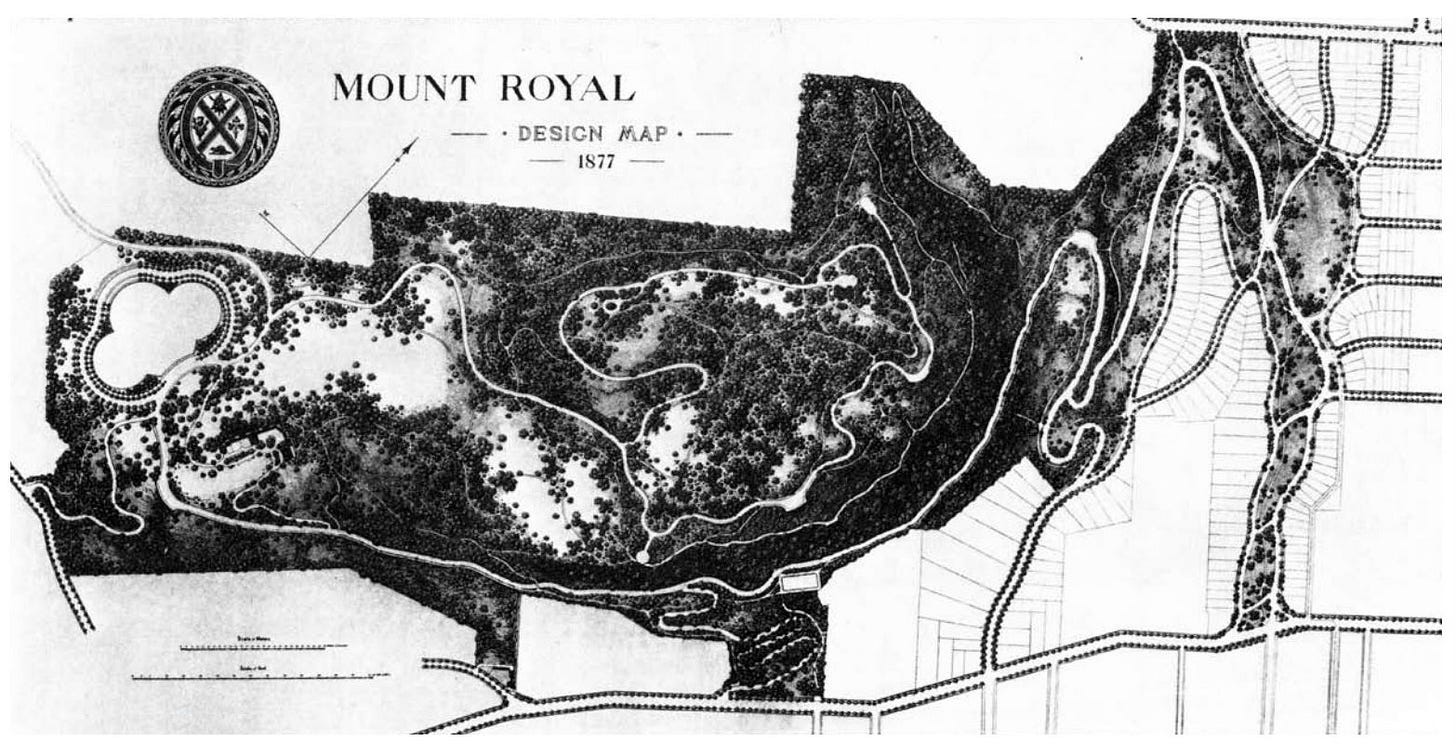

The Parc du Mont-Royal is the Central Park of my hometown. It was designed by Frederick Law Olmsted1, the creator of New York City’s best-loved green space, and it plays the same iconic role in the life of Montreal. Actually, Mont-Royal has several things going for it that Central Park doesn’t: paths through forest dense enough to fool you into thinking you’re deep in the sub-boreal zone (especially for those who snap on the cross-country skis in the winter); expansive, and atmospheric, cemeteries (bonjour-shalom, Leonard Cohen!); and the fact that it comes close to qualifying as a mountain: it rises to 234 metres (767 feet), and if you know where to look, you find a scree slope challenging enough to recall—briefly anyway—a scramble up a peak in the Alps or Rockies.

During the pandemic, when the gyms were closed, I got into the habit of riding my road bicycle up the curves and switchbacks of Camillien-Houde Way. It starts at Ave. du Parc, rises past a belvedere with a panoramic view of triplex rooftops and church steeples out towards the inclined tower of the Olympic Stadium, cuts through sheer rock faces, and then drops towards the gates to the rear entrance of the cemeteries. On weekend mornings during the lockdowns, it was a meeting place for MAMALs (Middle-Aged Males, All in Lycra), on their multi-thousand-dollar, carbon-fibre-frame racing bikes.

Now, I may qualify as a middle-aged male, but I hasten to note that I eschew Lycra. My bicycle at the time, a rusted-out 1980s vintage Bianchi, definitely put me outside this tightly-wound clique. In spite of my lack of pukka gear, I got pretty sporty—at the peak of the pandemic, I was cresting the mountain a half dozen times in a morning. (Some cyclists spend their days “Everesting”: completing enough up-down circuits—80, I think—to equal an ascent of Mount Everest.)

On some summer Sunday mornings, Camillien-Houde is closed to cars, with only cyclists and pedestrians permitted access. I love the tranquility that descends on the mountain when cars, trucks, and tour buses are kept off the road. On a normal day, the belevedere’s parking lot becomes a lover’s-lane-joint-smoker’s-rest-stop. (There always somebody who decides he—yes, almost always a he—is going to crank the stereo, open his doors, and share his execrable playlist with the rest of the world.) On those quiet Sunday mornings, I don’t have to worry about being clipped by a mini-van as I make the downhill run, at speed, towards the second turn on the way to Avenue Mont-Royal. It is here, by the way, that a white bicycle pays tribute to Clément Ouimet.

The young cyclist was killed in 2017 when he ran into a car, whose elderly driver had decided to do a U-turn in the middle of the road—right at that point where cyclists tend to be going their fastest on the descent. Every time I pass this tribute, I whisper the words “Salut, Clément,” which are stencilled on the asphalt. (Once I met his father, who had come to put flowers on the white bicycle on the anniversary of Clément’s death; when I told him I had bike-riding sons myself, we both broke down in tears.)

So when the news that Montreal’s Projet Montréal was going to permanently close Camillien-Houde Way to cars was announced this week, I had to pinch myself. There were to be no half measures: this would be a full closure of the road, which would be divided into two paths for cyclists and pedestrians—no cars allowed.

“The mountain is not a shortcut,” Mayor Valérie Plante announced at a news conference. “It’s a destination.”

It was only when I read the fine print that I reined in my enthusiasm: work on Camillien-Houde won’t begin until 2027, with the project due for completion in 2029. (And a lot can happen in municipal politics, including a complete regime-change, in a half-dozen years. By then, I hope I’m still capable of riding my bike to the top.)

I’ve heard all the objections to closing the road, and some of them have merit, and need to be taken into account. If cars aren’t allowed, elderly and disabled people might have trouble accessing the cemetery and mountaintop. (Actually, Remembrance Road will remain open, which will allow people to access the graveyards and parking lots that let you get to Smith House and the mountaintop cross; it will just be a slightly longer drive.)

A lot of the objections boil down to this: “I’ve always been able to drive over the mountain. It’s my favorite short-cut to the cafés of Mile-End. And besides, a pleasure drive is my right! That’s what the road is for!”

To which I say: Whoa, là! You may have gotten used to taking this road. But driving through a public park is not a right. On the contrary. The great Frederic Law Olmsted’s original plans made no provisions for motorized traffic. (Probably because automobiles were not much present on our roads, or any roads, in 1876.) The longtime mayor of Montreal, Camillien Houde, after whom the “Way” is named, famously said that a road would be cut through the park “over his dead body.”2 The unusual width of the road can be attributed to the fact that, starting in 1930, a trolley—a streetcar drawing electricity from overhead catenary wires—followed the route up the mountain, and the curves had to be engineered to accommodate it. By the way, you can still see the observation car, with its ornate grillwork and sculpted beavers, on display at Exporail, the excellent railway museum in St-Constant. Might be time to take it out of retirement…

I think the notion that public parks should accommodate cars goes back to the “parkways” of New York and New Jersey; in the 1930s, Robert Moses, the despoiler of so much of Manhattan and the Bronx, built curvaceous, tree-lined roads out to Long Island. The idea was that the lucky few who owned flivvers would be able to escape the city for a pleasant Sunday drive to Jones Beach. Public transit was discouraged; in fact, some overpasses were built so low that buses couldn’t pass below them. This suited people of Moses’s class very well.

Since then, car ownership became democratized, as mass motorization became the norm in the Americas. From Stanley Park in Vancouver to Central Park in Manhattan, urban green spaces began to choke with lines of exhaust-spewing cars. Camillien Houde died in 1958; Mont-Royal was opened to automobile traffic shortly thereafter.

Now the tide is turning: cars have been banned from Central Park, and Olmsted’s other jewel, Mont-Royal, is next on the list. I welcome the news, with this proviso: if you ban cars, you need to boost access by public transit. The very young, the very old, and people with disabilities shouldn’t be cut off from the pleasures of strolling amidst the spruce trees, or taking in the views. The city is promising that it’s going to boost the frequency of buses currently serving the route—and that’s essential to the success of this scheme, in my opinion.

I should note that I don’t think parks are necessarily for bikes, either. As much as I love the experience of riding a road bike on the mountain, I don’t think it’s a right—people on foot (or in wheelchairs and other mobility devices) should definitely come first, particularly over MAMALs intent on going downhill at 70 km/h. (And I turn into a grumbly old man when I meet people on dirt bikes using the forest paths on the mountain; not only is it not allowed, it’s also highly disruptive to people seeking a quiet time in nature, and it really degrades the trails. OK, end of grumble.) I hope a solution for cohabiting with people not on bicycles can be found. There’s enough space for bikes and walkers, and cyclists definitely need far less room than the drivers of cars. But let’s remember: people on foot were here first, and they should definitely get priority.

Before I sign off, I’ll leave you with a modest proposal. Until 1918, there was a funicular, or incline railway, that lofted Montrealers from near the George-Étienne Cartier monument to the peak of Mont-Royal. Why not bring it back? A restored funicular—like the one they still have in Quebec City—would become a tourist attraction in its own right, as well as a useful conveyance for people with limited mobility.

And man, what fun! I’d be one of the first in line—and that’s where I’d take every newcomer for a first glimpse of this amazing city.

It’s important to note that the original plans were by Olmsted, who died in 1903, but they were significantly modified during the layout of the park.

Not over his dead body, as it turns out, but beside it: the Honorable Monsieur Houde’s grave can be found in Notre-Dame-des-Neiges Cemetery.

Well said. I'm sure you've noticed the same battle, with the same arguments, happening with Toronto's High Park.