Getting into the Zone

Congestion Pricing is Coming to Manhattan. Will It Work in Other Cities?

It’s an idea whose time has come. (Arguably, it came a couple of decades ago, and the world has been slow to implement it.) In an urbanizing world, limiting vehicular access to densely-populated downtowns and central cities makes all kinds of sense.

By deploying bollards, sensors, and cameras, a city can make entire neighborhoods car-free, with the exception of emergency, service, and delivery vehicles, as well as local residents who can prove they’ve got access to off-street parking. Why should citizens have to breathe polluted air? Why should they fear for the lives of their children on their way to school? Why should they quake at the thought of a car-ramming attack—or other, more everyday forms of vehicular violence—when they’re trying to enjoy a meal at a sidewalk restaurant terrace? Attaching a price to mobility, especially privileged forms of mobility like private vehicles, makes a lot of sense in a time when we’re trying to reduce the use of fossil fuels and encourage walking, cycling, transit, and other forms of sustainable urban transport.

These zones take many forms. One of the first cropped up in Singapore, an island city-state where street-space is at a premium. Since 1975, drivers have had to pay a fee to enter its business district; these days, overhead gantries charge an electronic toll to devices in cars, which all drivers are required to have. (Car ownership in Singapore is limited to the wealthy, as vehicle permits cost a minimum of $71,000; fortunately, its transit system is excellent.) In 2006, Stockholm launched a six-month pilot “congestion pricing” program, which led to a 20% drop in traffic in its central business district; a referendum has since made it permanent. The Central London Congestion Charging Zone, which initially covered around 8 square miles, kicked off in 2003. The standard charge to enter the zone is now £15.

This week, Giuseppe Sala, the mayor of Milan, one of Europe’s most polluted cities, announced he’s considering banning cars from the Fashion District: “I am not an antagonist of capitalism, but honestly seeing the parade of supercars in the centre which they then can’t park can’t continue.”

In Europe, there are now at least 300 cities with these kind of traffic-limited zones. I’ve been in small hill towns in Italy, where traffic is limited to buses, taxis, and local residents; the lack of private vehicles has allowed for a return of pedestrian-dominated streets, and the agreeable practise of the passeggiatta, the evening stroll. Many of these zones are framed as Low Emission Zones, or even Ultra Low Emission Zones: certain electric vehicles are allowed to enter free, or at a lower rate, but diesel cars and trucks are charged hefty fees.

Major cities in Canada and the United States have not embraced these zones. Until now. New York City is set to be the first: as of next year, private vehicles could be charged $9 to $23, depending on the time of day, to enter Manhattan south of 60th Street. Almost three quarters of a million vehicles enter this part of the city every day, and average speeds have slowed to just 7.1 miles per hour. On my last few visits to New York, congestion has seemed worse than ever, and my perceptions are backed up by the reports of residents, who say, more than ever, the city remade by Robert Moses has become a martyr to the internal combustion engine.

The most successful examples of congestion pricing are one that pour the revenue back into transit—and smart cities make this connection very clear to residents. This was the case in London, whose congestion zone coincided with the purchase of 300 new TfL buses; the fees have continued to improve surface transit, which, with less competition from cars, can move more efficiently. This is the plan, too, in New York, where congestion fees will go directly to capital costs for the MTA. And God knows, the beleaguered, leaky subway, and the glacially-slow city buses (the recipients of annual “Pokey” and “Schleppy” awards from the Straphangers Campaign) can use all the help they can get.

Major opposition is coming from Staten Island, a borough that is short on transit and long on cars, and New Jersey1, which in July sued the federal government to stop congestion pricing, as reported by the NY Times, “over concerns that it would place unfair financial and environmental burdens on the state’s residents.” The idea is that congestion, line-ups, and idling cars would be shifted to the other side of the Hudson. As some commentators have suggested, purported concern for the environment concern is the last resort of the self-serving scoundrel; what the critics really want is to keep on driving downtown, for free. We’ll see how far this gets; with strong support from New York’s governor, Kathy Hochul (Albany traditionally being on the side of drivers), the stars seem aligned for this to come to fruition.

Now, here’s the big hope of sustainable transportation advocates: once North Americans see congestion pricing in action in NYC, it will awaken a hunger for similar zones in the rest of the continent.

I can see this working in many other cities, including Boston, Philadelphia, Portland, and San Francisco, which have relatively compact (and in some instances, horribly traffic-choked) cores. Not so much in Los Angeles, Houston, Salt Lake City, Indianapolis, and other auto-centric cities whose growth mostly occurred after the post-War automobile Big Bang.

And I can see it happening in some Canadian cities. One that comes to mind immediately is Quebec City, whose compact historic core, with streets laid out in the 17th and 18th centuries, has always struggled to accommodate cars. (Its transit system could also use a serious revenue boost.) This could also work in Vancouver, which was spared downtown freeways by vigorous protests, and parts of Toronto, though its downtown—like Montreal’s—has been throttled by city-crossing expressways.

Yes, there is a difference between North American and European cities. Many of the latter are medieval (and even Roman) in origin, with centers built for walkers, rather than wheeled vehicles. New York City, for all its “New World” character, is an anomaly on this continent—it’s a place whose compactness and human density make it more like Paris, or Milian, or Barcelona, than like Phoenix.

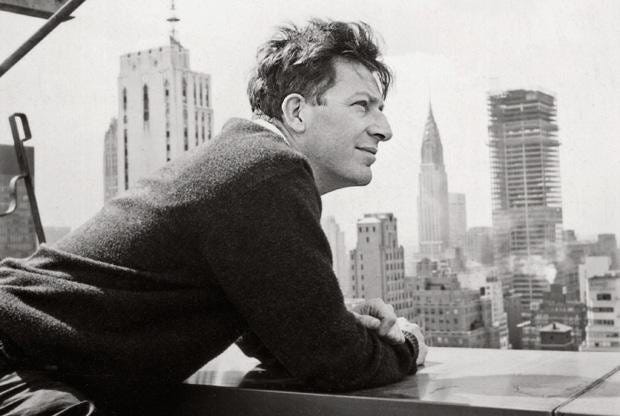

Paul Goodman, the great philosopher of education, expressed it well in a manifesto from 1961, “[Manhattan] can easily be a place as leisurely as Venice, a lovely pedestrian city. But the cars must then go.”

It’s taken over sixty years, Mr. Goodman, but we might be on the brink of realizing your vision. Here’s hoping that it spreads beyond the limits of Gotham.

For a good summary of the struggles to bring congestion pricing to NYC, listen to the always entertaining “War on Cars” podcast, especially this episode featuring Diana Lind.

when I subscribed to Joel Epstein's "Cities & Transportation" I didn't realize it included your work as well. Please unsubscribe me.

Sandord S Zevon, MD