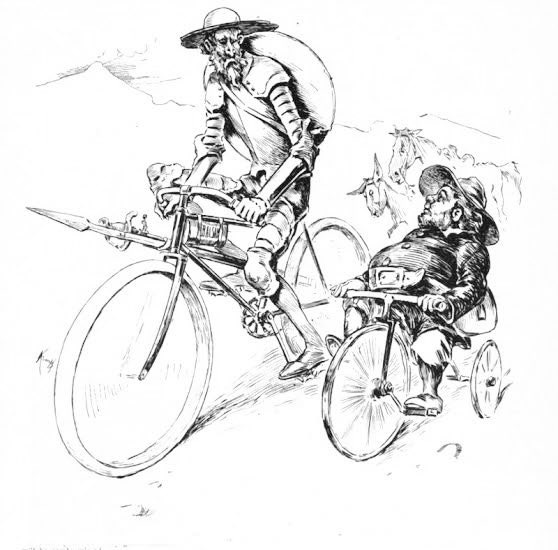

The Don Quixote Syndrome

On Being an Advocate for Public Transit When the Public Realm Is Disintegrating

My book Straphanger: Saving Our Cities and Ourselves from the Automobile was published over a decade ago. At the time, I was optimistic about the future of transit in North America. Gas prices were running high, as was concern over global warming (which was then also known as “climate change,” as opposed to global heating and the climate crisis).

There was a steady rise in transit use, with the New York subway clocking year-over-year increases, and beating ridership records that had stood since after the Second World War; Los Angeles was building new metro lines; San Francisco was a solid bastion of bicycle-transit-pedestrian infrastructure. I visited Portland and Philadelphia, two cities that, thanks to their “good bones,” struck me as being primed for great advances in non-automobile transportation.

Earlier this year, I was asked to give a keynote in Las Vegas for a meeting of the American Public Transportation Association (APTA). I spent several weeks catching up on what was happening, post-COVID, with transit on this continent. The situtation in major Canadian cities—I live in Montreal—was actually pretty good. Ridership, which had plummeted during the pandemic, was returning to pre-2020 levels. Concerns about “transit death spirals” (Montreal was cutting back on its network of 10-minute headway bus routes) were there, but the general feeling was that this was temporary.

And there were, and are, a lot of exciting things happening in Canada’s major cities: the opening of the REM, the automatic elevated electric “light metro” in Montreal; Toronto’s massive (if slow-moving) transit expansion, which includes the Ontario Line, a new crosstown light rail, and the electrification of their commuter rail network; Calgary’s expansion of its wind-powered C-Train light rail system; and the Broadway Subway, which, along with the Skytrain, the Canada Line, the Seabus, and a truly expansive bus system makes Vancouver a city to beat for transit coverage, frequency, and reliability in the Americas.

When I did a survey of developments in the US, though, good news was harder to come by. In my presentation, I highlighted the opening of San Francisco’s Central Subway and the Van Ness Avenue BRT. In DC, the Silver Line to Dulles airport finally opened, as did the Crenshaw Line in LA. New bus rapid transit lines were launched in St. Petersburg (Florida), Birmingham, and Portland. Phoenix launched the 4-mile-long Tempe Streetcar, and Seattle opened the Line T streetcar to Tacoma. And Boston, whose mayor is the transit-loving, and transit-riding, Michelle Wu, saw the opening of the Green Line extension and the South Coast rail project.

But talking to the people who run, and advocate for, transit systems in the US was sobering. The aftermath of COVID came with a big drop in ridership. Remote work and video calls meant that people had stopped coming into downtown offices, or were only commuting a couple of days a week. Hollowed-out downtowns meant fewer riders, which meant less revenue, which meant less money for security. I heard horrific tales of vandalism; one father, who tried to walk the walk by riding the trains run by the agency he worked for, had seen people pull guns—while he was with his child on the platform—three times in one week.

In places that used to be transit-promised-lands (well, in an American context), like Portland, Oregon and San Francisco, riding transit just doesn’t feel safe for many people these days. There aren’t enough other riders around—and not enough “eyes on the street.” There are cameras, but no security guards, and very little enforcement. I’m not trying to minimize the insane militarization of law-enforcement in many jurisdictions, and the beatings and murders that led to calls to de-fund the police. But a well-managed (but not necessarily heavily armed) constabulary is crucial to keeping complex 21st-century cities functioning.

For public transit to work, in other words, you have to have a functioning public realm. It’s easy to say: “Look at Switzerland! Look at Japan! Everybody, from unaccompanied kids to grandparents, rides the trains! We should be more like them!” Well, when you don’t feel safe waiting on a stroad for a bus, which might come once an hour, or you’ve had to get off the streetcar because somebody pulled a knife, again, or been forced out of a New York subway station by fucking rainwater, you’re going to think twice about riding transit. When a society stops being able to secure the public realm, people will opt for private alternatives. And of course, that’s a vicious circle: each person who gives up, and finds away to get where they need to go by car, removes another rider, and source of revenue, from the public transit system. That suits people like Elon Musk, who sell cars, as well the sense of insecurity that makes those glassed-in bubbles seem like the only safe choice.

Look, as a transit advocate, I’m all in. I walk the walk, by which I mean, I ride the bus (and the metro, and the commuter rail, and my bicycle). I don’t have a car in my driveway, because I don’t own a car—never have—and we don’t have a driveway to put such a thing in. But the only reason I can do that is that I live in a transit- and bicycle-rich environment, in a city where the public realm is still in pretty good shape. That’s the case, for the time being, in most Canadian cities. But it’s not true everywhere. Things can, and do fall apart. And where that’s happening, opting for the private realm (ride-hailing, taxis, private automobiles, jitneys, company buses) suddenly makes a lot of sense. In a context of social division, when hate is on the rise—Islamophobia, anti-Semitism, anti-Asian COVID-era hysteria—the public realm can be a very dangerous place to be.

So, I’m no Don Quixote; I won’t tilt at windwills, or wait 45 minutes in the cold for a bus that might or might not come, in the name of defending a principle. I live in the real world. If I lived in a place where riding transit felt like a threat to life and limb, or where going underground started to feel like an existential threat, I’d make the rational transportation choice: I’d find another way to get to where I needed to go. I’m still fit enough that, in almost every case, that alternative would be a bicycle—but I don’t blame individuals in such situations for opting for cars. The blame almost always lies elsewhere.

Civic insecurity is a mind-bendingly, Freakonomically complex phenomenon; the solutions are dauntingly multi-pronged. But, though I’m an ardent proselytizer for transit, I’m not going to get on anybody’s case for opting out of the public realm because they don’t feel safe. My strategy is to accentuate the positive—those places that are getting sustainable transportation right.