Small Cities, Big Transit

Turns Out You Don't Have to Be Chicago-Sized to Have Rail Rapid Transit

Several times in the last few years, I’ve arrived in a relatively small European city, and been shocked to find the sign for a metro—an underground urban rail system—welcoming me outside the train station.

The first time was in Brescia, in northern Italy. I’d come there on the way to Lake Garda, where I was headed to write about Italy’s #1 olive-tree pruner. (Sorry, straphangers, this writer does not live by transit alone!) As I walked out of the train station, I noticed a bikeshare stand next to the bus stops—already a good start.

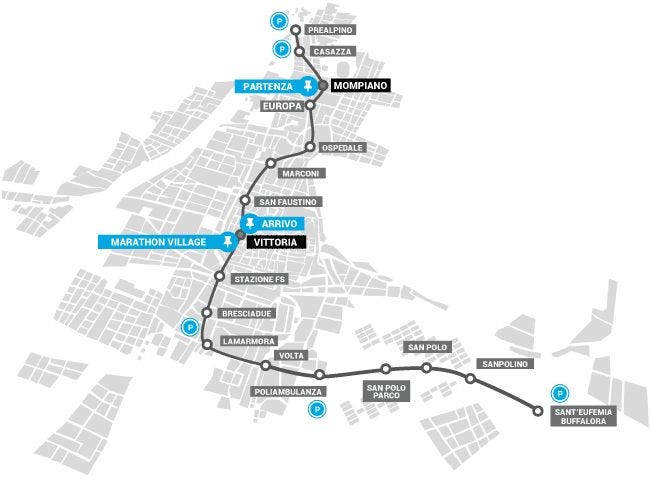

And then I realized there was an actual metro station in the same piazza, something I hadn’t been expecting at all. After all, the population of Brescia is just 194,000. Yet here was a relatively new 17-station light metro line.

The trains are driverless, and run underground and above outside the city center, with headways (wait times) of as little as 3 minutes. First train leaves at 5 am, last at midnight. I didn’t spend a lot of time on the metro, which opened in 2013, but it was a pretty smooth ride; I later realized the trains were identical to the ones I’d ridden on the Copenhagen metro.

The following year, I spent a few hours in the center of Málaga, Spain before taking an intercity bus to Cádiz (to research a book chapter on garum—yet another food story!) This is where international flights touch down for package trips to the Costa del Sol—and it’s also a visual arts center, with an excellent Picasso museum. I wasn’t expecting much from the place, but as I was dragging my wheeled suitcase around in a jet-lagged daze around the downtown, I noticed that, just next to a bikeshare stand…was the entrance to a metro station.

Now a metro is something I expect to find in northern Spain, but in my experience the cities of Andalucia can be pretty light on transit. (That said, Seville has made itself into one of Europe’s great bicycling cities in the last decade, with hundreds of kilometers of bike path.) Yet in Málaga, with just half a million residents, there is a two-line metro with 19 stops. In fact, it’s a “semi-metro,” in which tram-like light rail vehicles run underground to the railway station, and at-grade outside the historic center. (Click on the link for an interactive panorama of a station.)

France is famous for its new urban tramway systems, but it also has small cities with outsized rapid rail networks. One is Lille; another is Rennes, the lively university town in Brittany. With a population of just 360,000, it has a two-line metro system with a whopping 28 stations.

Until 2008, Rennes qualified as the world’s smallest city with a metro system. (Actually, there is a village with a metro of sorts. Serfaus, in the Austrian Alps, elev. 1,429 meters, has a single-cable underground U-bahn that travels on air cushions and has been operating since 1985.) Rennes was then supplanted by Lausanne, a city on the shores of Lake Geneva in the French-speaking part of Switzerland, which also has a two-line, 28 station rail transit system.

I’d learned Lausanne had its own metro after hiking up a mountain at the Swiss Jura. Eating rösti in a little mountaintop restaurant, I struck up a conversation with the people at the next table; one of them, it turned out, was responsible for designing the Métro de Lausanne. He confided that it was extremely politicized: one faction wanted new stations (because even more stations were being planned!) to look like real urban rail stations. The other wanted them to blend into the cityscape by having their entrances incorporated into existing buildings. From a North American perspective, I told him, this was a nice problem to have.

I got to spend a couple of invigorating days exploring Lausanne. Great food—lots of “chewy” white wine and lake fish—and amazing museums, including the Maison de l’Art Brut, a collection of outsider art in interconnected villas. I never once considered getting in a taxi (in spite the rain and a lot of hills). This is a transit-rich environment. There were e-bikes and regular bikes for rent at bikeshare stands; ubiquitous articulated trolley buses; and of course, I’d arrived by intercity train, which are so frequent in the Swiss Vaud they feel like subway trains.

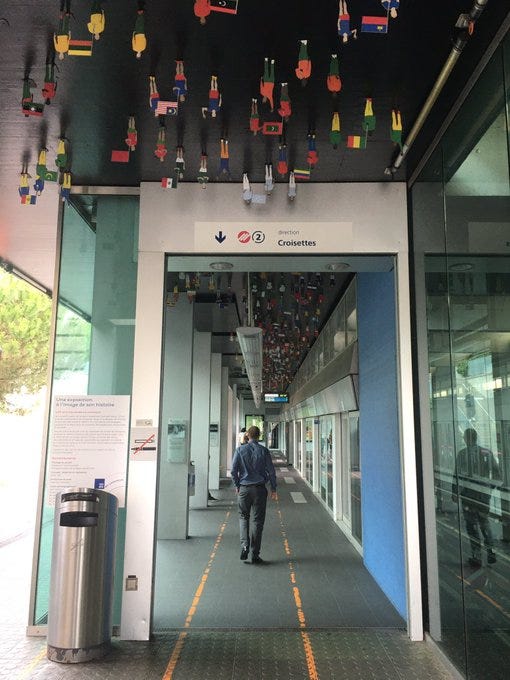

The Métro de Lausanne is a bit of an oddity. The second line, the north-south M2 replaces a historic incline railway, and runs automatic trains on rubber tiles up a 12% grade. It has a dozen stations, and here’s a nice detail: when the train arrives at certain stations, the announcements come with themed sound effects. For example, ticking of a stop watch at Ouchy-Olympique, the sound of horses hooves and neighing at Délices. It meshes with the very successful M1, which runs light rail vehicles on an 8-kilometer east-west route.

Take a closer look at the transit map of the Lausanne region. The options, including regional, intercity trains and buses, are enormous. They include two lines of urban rail rapid transit—for a population of 139,000.

Contrast this with Arlington, Texas, pop. 390,000, which not only has no rail transit stops, but also zero bus routes. In fact, when it comes to transit: nothing. Y'all gotta drive...

According to the standard thinking, especially in the US and Canada, cities the size of Brescia, Rennes, and Lausanne are too small for urban rail. The best you should reasonably hope for is a bus rapid transit line. This is the story I heard in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, whose population is around a quarter of a million, and was having trouble convincing citizens that even a BRT line was worth building. Don’t get me wrong, BRT is great, and may well be the best solution for the more spread-out cities of the west, and have a role to play in big cities like Los Angeles and Montreal too.

But my travels in Europe have shown me that I’m right to scoff when somebody says a given city is “too small” for rail transit. The only thing really too small—at a time when politicians and planners need to look at all options for decreasing emissions and sprawl—is the scope of our imaginations.

_____

I hope you’ll consider becoming a paid subscriber to my Straphanger Substack. Almost everybody who’s signed up so far is a “free rider.” No shame in that! But to keep this train going, I’m going to need at least a few people who are willing to help out by chipping in, even with a low-priced monthly subscription. (I’m talking the price of two taps of your farecard here!)

very interesting, including the stops to read about the Sergio Cozzaglio and his trees + olive oil and Flor de Garum.