Interurban Nations.

A requiem for North America's overhead wires, and the tracks that led into the woods.

I’ve long been fascinated by the traces, still visible in rusty stretches of track in asphalt in city streets and alongside country roads, of the electric transit networks that operated in much of North America a century ago.

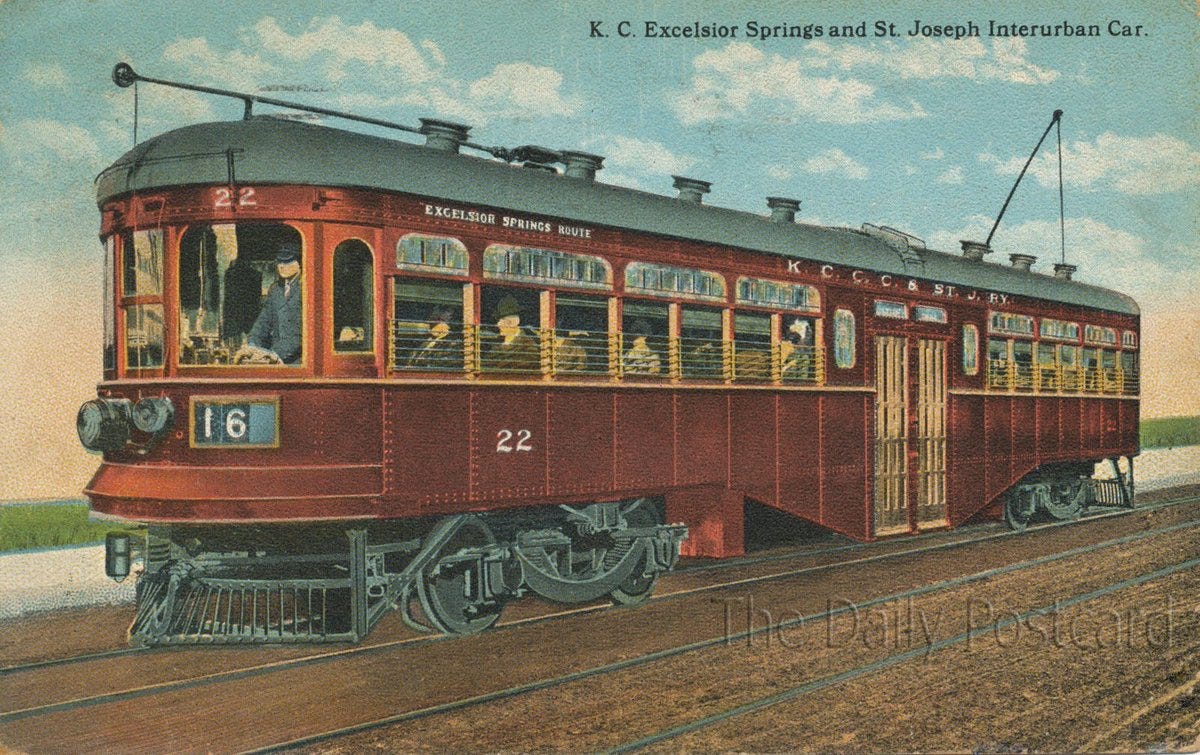

By 1920, the network of interurban trains in the United States was so dense that a determined commuter could hop interlinked streetcars from Waterville, Maine, to Sheboygan, Wisconsin—a journey of 1,000 miles—exclusively by electric trolley.

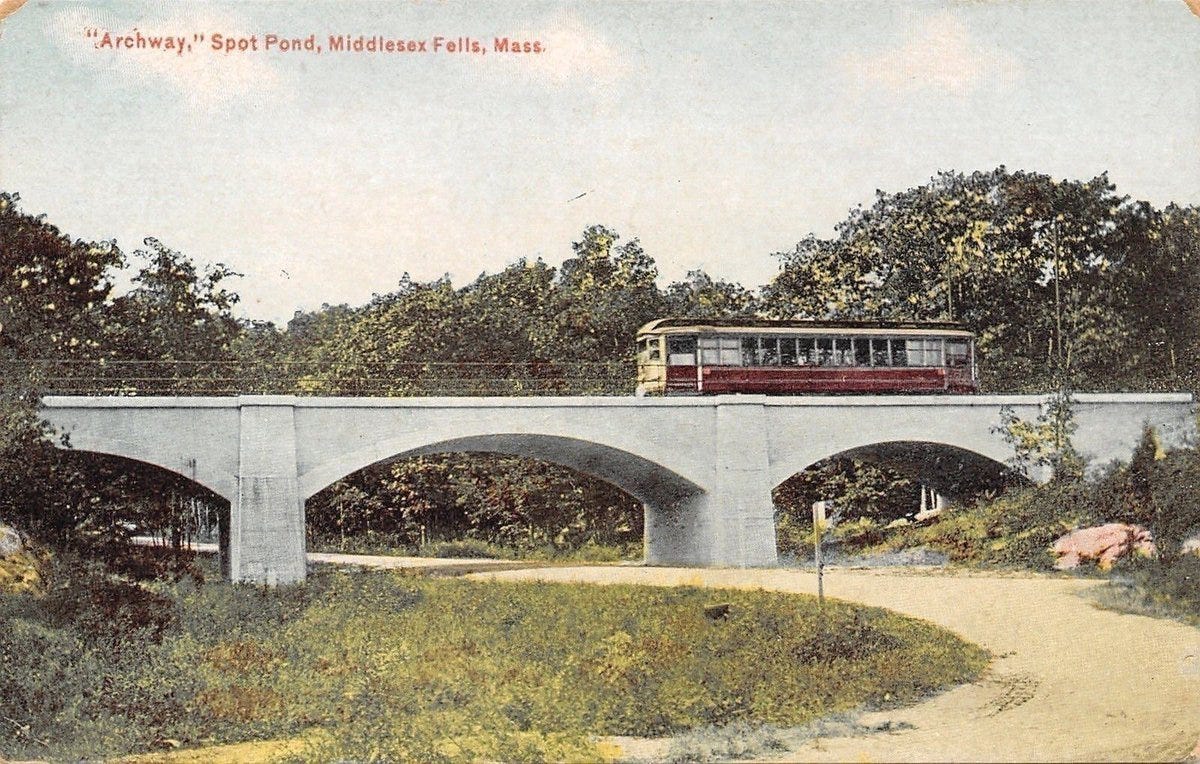

The tracks, and often the wires, extended deep into forest and farmland, making the railroads de facto intercity highways; after nightfall in the countryside, farmers would signal drivers to stop by burning a rag next to the track.

By the end of the First World War, streetcars and interurbans had become the dominant mode of urban transportation in North America, carrying 11 billion passengers a year.

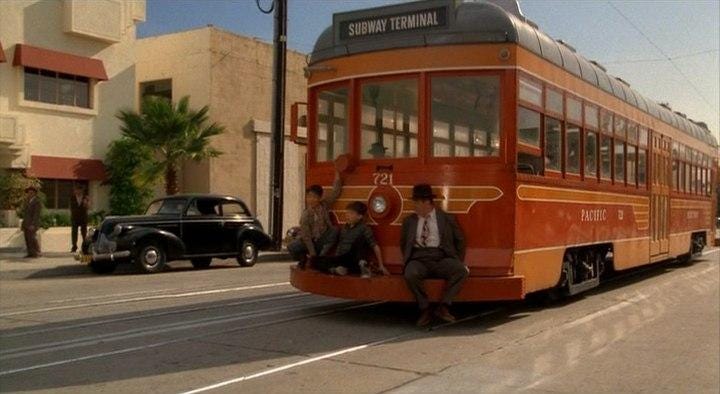

What happened? In the 1920s, cars really started clogging the streets and highways. The streetcars and interurbans, once quick and efficient, got mired in traffic, becoming the most sluggish things on the road. GM, Firestone Tire, Standard Oil of California, and other representatives of “motordom” (the term transport scholar Peter Norton uses to describe the concatenation of interests that led to car dominance) hurried things along by promoting "bustitution": making sure steel-wheeled trains were replaced by rubber-tired buses, which became the slowest things on the road. Remember that movie Who Framed Roger Rabbit?, which was set in a fantastic, bygone LA? Its private dick hero Ed Valiant wasn’t wrong when he jumped on a streetcar and said: "Who needs a car in LA? We've got the best public transit system in the world!"

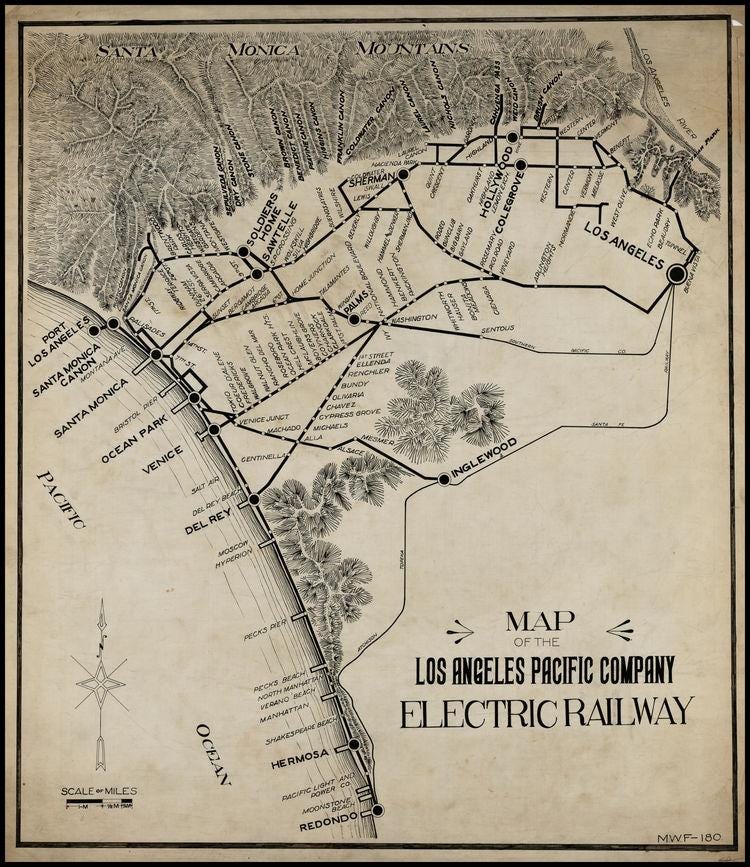

Transit historian Spencer Crump noted: "Of 13 cities in Los Angeles County in 1919, all but one was located on a Pacific Electric line." Before the freeways came, Los Angeles, with its Yellow Cars (streetcars) and Red Cars (the big interurbans) was the transit city par excellence.

There was almost no city, no matter how small, that didn’t have an electric rail network—here’s the first streetcar to run in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, in the height of its boomtown years. Five thousand people rode the new streetcars on the first day of service, Dec. 30, 1912, in spite of the fact that there was a full-on blizzard blowing.

I love the chapter in E.L. Doctorow’s novel Ragtime that describes a Jewish father's epic ride with his daughter from Union Square in New York City to Boston, entirely by streetcar and interurban. "There was in these days of our history,” wrote Doctorow, “a highly developed system of interurban street railway lines. One could travel great distances on hard rush seats or wooden benches by taking each line to its terminus & transferring to the next."

“Tateh [the father] didn't know anything about the routes, he only planned on going as far as each streetcar would take him."

The old electric cars, which had helped create “streetcar suburbs” (still among the most walkable, sought-after neighborhoods in many cities) ended up piled in scrapheaps, and the tracks were torn up or paved over. North America turned away from a sustainable, electric-powered form of transport and the “love affair” with the gas-powered automobile blossomed. We are all forced to navigate the dehumanizing landscape its created.

For the time being, the future is being written elsewhere. (As in France, where in Orléans, below, and scores of other cities in Europe modern tramways are running on the streets.) But never say never again...

If you have photos of traces of North America’s interurban history—old overpasses and bridges, branch lines, tracks in the woods—I’d love to hear about them, or see them, if you have photos, in the comments.

Excelsior…